As soon as something better, more powerful is invented, progress ruthlessly replaces traditional technologies in the twinkling of an eye. Rammed concrete also suffered this cruel fate once reinforced concrete was invented. Quite rightly, but still a bit in the wrong, because, although rammed concrete has many disadvantages compared to its well-proven reinforced successor, it also has certain properties that make it stand out and make it interesting for certain projects. After almost a whole century of disregard, an iconic building made people aware of its properties once more. Since then it is again in demand when a particular aesthetic charm is required.

© I, Kateer [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Common

The origin of the technology for producing rammed concrete is in the pisé process, in which clay was rammed onto walls, developed at the beginning of the 17th century in France. This technique was developed in 1820 by Francois Martin Lebrun to become rammed concrete. In this method, a stiff, earthy, moist mixture of natural stones and cement is placed into form at a thickness of a maximum of 15 to 25 centimeters and rammed for so long until the surface is closed and a moisture film appears on it. Before the next layer can be applied, the first must harden for about a day and then it is roughened, cleaned and moistened.

Revival of a forgotten material: Thanks to Zumthor!

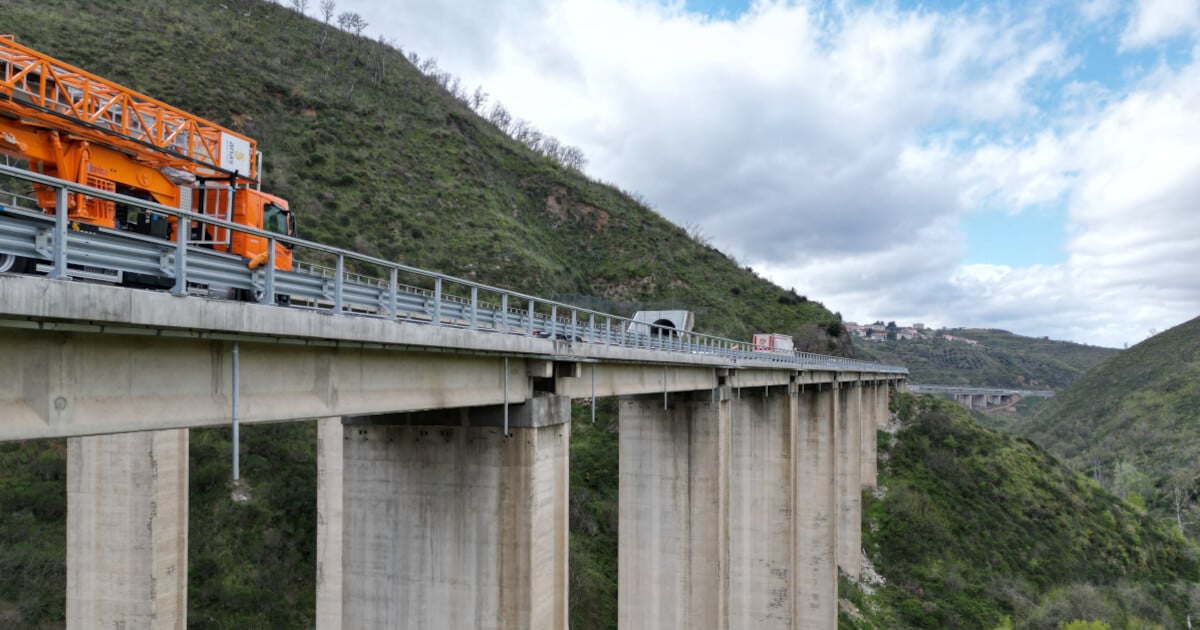

In addition to buildings, foundations and bridges, in particular, were built from rammed concrete up to the beginning of the 20th century. Then came reinforced concrete which marginalized the rammed compound material with tremendous compressive strength but poor tensile strength for about 100 years. During this period, virtually no construction work was carried out with rammed concrete. This changed when a couple named Trudel and Hermann-Josef Scheidtweiler approached the Swiss star architect, Peter Zumthor, in the mid-2000s with the desire to build a chapel on their field at Wachendorf in the Eifel region.

© By Thomas von Arx (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

They were able to win over Zumthor for their project, but he initially regarded the chapel (which was intended to be consecrated by the Swiss peacemaker saint, St. Nicholas of Flüe, also called Brother Klaus) as a small side project. However, in the end, by his own admission, he put almost as much work into the small church building as he did into the Kolumba Diocesan Museum in Cologne, which was built at about the same time, and developed an iconic building that would go on to achieve world fame. The twelve-meter-high tepee-like rammed concrete tower was erected over a period of two years between 2005 and 2007 with the help of a number of volunteers who rammed the material layer by layer with their hands and feet.

Archaic and resistant

Although it is a thoroughly modern building, the chapel appears strangely primitive due to the special look of the rammed concrete and its idiosyncratic shape. Thanks to Zumthor's monolith, many architects were drawn to the building material with its archaic look reminiscent of naturally occurring sediment layers. In addition to its appearance, some other interesting properties were re-discovered during the work. The compaction of the concrete, generated by enormous compression, prevents the formation of cracks and leads, at the same time, to a low susceptibility to shape change, making rammed concrete particularly suitable for monolithic and durable construction method.

Conclusion

In the construction of bridges or extremely high buildings one would prefer not to rely on the not-too-tensile "old concrete". However, thanks to Peter Zumthor's retrospective material, it is now increasingly being used for projects in which it is structurally harmless and its archaic appearance especially seems to make sense. For example, as a complement to medieval stone structures. In this contex, Max Dudler’s prize-winning visitor information center for the Bielefeld Sparrenburg Castle uses certain aggregates to achieve a color which closely resembles that of the existing building. In such perfectly constructed, rammed concrete buildings, life is a force even without reinforcement.